On Thursday, two students and I will present a workshop on “Exploring Student-Designed Assessment” at the Pan-Canadian Conference on Universal Design for Learning. If you’ll be at the conference, please join us!

We hope to take UDL’s “multiple means” to a new level: how much of the assessment strategy can students design themselves? We’ll explore how Standards-Based Grading can be used to turn over that control, by letting students apply for reassessment when they’re ready, as often as they are ready (up to once per week), and in the format that they choose. For a more detailed exploration of how this connects to UDL philosophy, see my previous post.

Why Should Students Design their Own Assessments?

Tim Bargen, one of the students with whom I’ve co-designed this workshop, values the aspect of UDL that prioritizes offering this flexibility to all students, not just those with a diagnosis or documentation.

“The idea of ‘Tight Goals, Loose Means’ is important because [everyone] has the same freedom. When doing things differently, rather than feeling a need to hide it, it’s easier to discuss the way you are doing things with classmates and share ideas. ”

He also values the opportunity to control what he spends more and less time on, and the ability to learn by reassessing skills as often as he chooses. “It allows students with differing prior knowledge to focus on the parts of the content that are difficult for them. It’s simply more efficient to ‘learn the hard way’ [by making mistakes and trying again.] It allows the student to more readily identify the areas they struggle with.” He also points out that “reassessment” doesn’t just help you fix your mistakes in physics; it can also help you fix your “mistakes” in time management and other life skills. “Mistakes” could be taken to include those made outside of the classroom, which prevent the student from engaging in or showing up for classes.”

What do we mean by “Student-Designed Assessment,” and how do we do it?

We’ll describe 2 techniques that combine UDL and Standards-Based Grading, give participants some time to try one of those techniques, and then take questions. You can follow the structure of the workshop using the handout, in

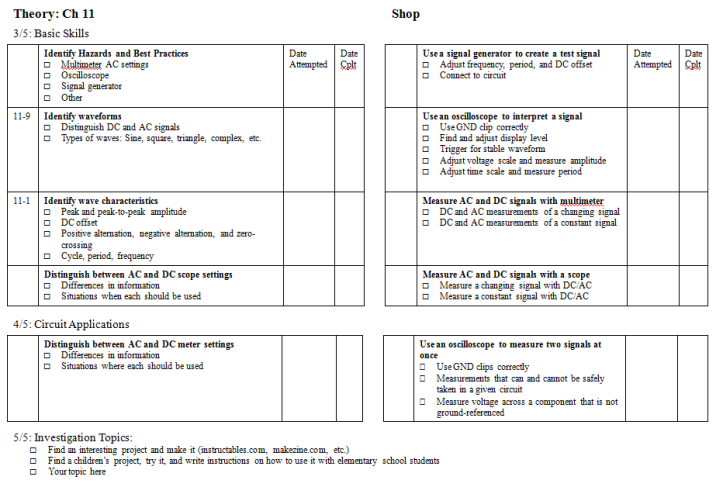

1. Skill Sheets

Description and Example (screencast of handout pp 2-3)

Skill sheets are a tracking tool that students use to figure out what they’ve completed, what they need to work on, and what’s coming up next.

The magic happens when they are used in the context of Standards-Based Grading. This means that students can choose for themselves when and how to demonstrate their mastery of each skill.

Description (screencast of excerpts from How I Grade)

2. Format-Independent Rubric

Description and Example (Screencast of handout pp 7-11)

If I’m going to encourage students to choose their own format for demonstrating mastery, I have to be ready for anything. No one’s written a folk song about electrons yet, but I’m looking forward to that day. In the meantime, I need a rubric that is as format and content independent as possible.

For example, I use a single rubric for anything that students build – whether they submit a report about it, a video about it, or demonstrate it to me in person. It must include:

- Predictions of electrical quantities

- Measurements to test all predictions

- Comparisons of predictions to measurements

- Discussion of what happened, what could be causing it, and how it connects to other things the student has learned

This removes the burden of creating a new rubric for every new thing a student decides to do. In the workshop, we will present example templates and invite participants to design their own.

We look forward to meeting you and exploring these topics together. See you soon!

http://www.songsforteaching.com/scienceinsong/electrons.htm

Hah. That’s great, and might be just the thing to help students start noticing the “single-file-chain-reaction” assumption that many people (and many explanatory diagrams) fall into.

[…] Exploring Student-Designed Assessment using Standards Based-Grading | Shifting Phases […]

I was thinking of you today. Just stopping by to let you know, a digital hug of sorts.